A wonderful woman called Lindy from Cape Breton first contacted me in February of 2008. She had found my information on rootsweb and sent an email to make a point of connection in our research on the McDonnell/Sergeant/Harrower family. Lindy had compiled a whole series of records of the family, from Frontenac and Lanark counties all the way back to Scotland. She was so generous in an email stating “I have PAGES of info for you!!!”. Some people say that and just fall back into the great electronic abyss. Lindy literally sent a whole manilla envelope for me to sort through. This is like coming into an attic treasure (without the cobwebs): although she has marked out different records and maps in blue post-it notes, I still find myself wading through a very deep lake of names, dates and blurry photocopied faces. I took an initial look after she sent the papers to me, but with my emerging career and other obligations in everyday life, this research was put on the back burner. Now that I have decided to actively blog about what I’ve been doing with my spare time over the past decade, I have a reason to splay all of these papers across my dusty wooden floor. I am using this blog to do my initial inventory on this booty.

A wonderful woman called Lindy from Cape Breton first contacted me in February of 2008. She had found my information on rootsweb and sent an email to make a point of connection in our research on the McDonnell/Sergeant/Harrower family. Lindy had compiled a whole series of records of the family, from Frontenac and Lanark counties all the way back to Scotland. She was so generous in an email stating “I have PAGES of info for you!!!”. Some people say that and just fall back into the great electronic abyss. Lindy literally sent a whole manilla envelope for me to sort through. This is like coming into an attic treasure (without the cobwebs): although she has marked out different records and maps in blue post-it notes, I still find myself wading through a very deep lake of names, dates and blurry photocopied faces. I took an initial look after she sent the papers to me, but with my emerging career and other obligations in everyday life, this research was put on the back burner. Now that I have decided to actively blog about what I’ve been doing with my spare time over the past decade, I have a reason to splay all of these papers across my dusty wooden floor. I am using this blog to do my initial inventory on this booty.

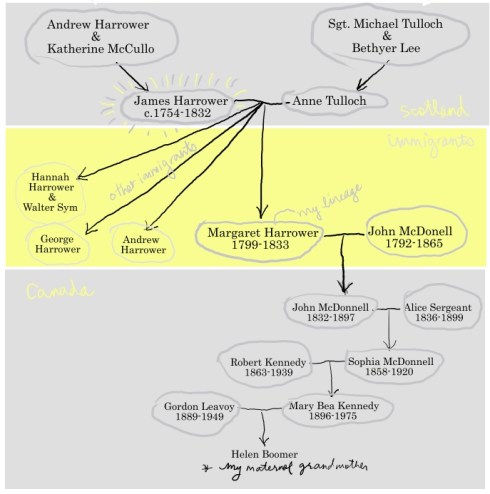

The starting place for this package is a photocopy of an essay called James Harrower, Royal Highlander by Barbara R. Knutsen of Kelowna BC and Barbara & Donald Harrower of Bradenton, Florida (1991). This is a gorgeous read: with familiar language it tells the story of one of the earliest known ancestors in the Harrower family. I was so enthralled at the way this story was told and hope to have the same effect in my own family tales with some practice. To make sense of the people who I am discussing in this blog entry, I would first like to sketch out a rough and basic tree:

The above mentioned essay describes James Harrower who is my 5th great grandfather in my maternal grandmother’s family, the last of the Scottish ancestors in this line who stayed in that country’s highlands. A description of the man reveals that he was a highlander from Crieff, 5’7″, with grey eyes, brown hair and fair skin. He was also a soldier with the British Army who was caught up in that country’s fight against American rebellion during the Revolution. I would like to paraphrase my understanding of the essay here to share all of its meaty bits. This by no means is all that is told, and I recommend that those who are seriously interested get their hands on a copy of the original.

In 1774, as a young man (20 years old), James Harrower entered the 42nd Regiment of Foot, known as “The Royal Highlanders” or “The Black Watch”, which had grown for service overseas. His involvement took him from Cork to a posting in the reserve British forces for the Battle of Long Island in America, which was the first major battle after the Declaration of Independence. During this battle, in September of 1776 on York Island, James was wounded on both his right hand and foot. Despite this he remained a member of Captain John McIntosh’s company for another 3 years in the Long Island/New York area.

In 1784, at age 30, James was admitted to the Royal Chelsea Hospital back in Scotland, having been “left lame” from his wound to the foot during his 10 years of military service. He was an outpatient, and was assigned to Garrison duty at Fort Augustus in the rugged Highlands of Scotland, where he helped to “curb the rebellious Scots”. During this year he was promoted from the rank of private to corporal in Capt. Elliot’s Independent Company of Invalids. It is also during this stationing at Fort Augustus that James Harrower married Ann Tulloch, daughter of Sgt. Michael Tulloch in 1786.

James and Ann Harrower had 10 children together who were all baptized at Bolskine parish: Catherine (1787), William (1789), James jr. (1792), Anne jr. (1794), Charles (1797), Margaret (1799), Elizabeth (1801), Hannah (1803), George (1805), Andrew (1807). By 1797 after the birth of their 5th child, James was again promoted, this time to the rank of Sgt., and served another 5 years with The Royal Invalids. His extensive military career continued further, where he later served the 6th Royal Veteran Battalion in Fort Augustus, concluding his posting as paymaster in 1810 when he retired. In all, James Harrower had served in the military for 36.5 years before he was discharged at Fort George as a man in his mid-fifties. He was given a pension that took him back to his birthplace of Crieff as “beer marching money” (14 days pay of 1 pound, 12 shillings, 8 pence).

In 1818, 8 years after the trek home, his daughter Margaret (my fourth great grandmother) married John McDonnell. That same year, they made the decision to move to Upper Canada to homestead: likely fueled by James’ stories of the new world. They stayed in Glengarry county for several years where they had their first 5 children, and then settled in Lanark where three of her siblings had been granted land.

Three other children of James and Ann soon followed their sister to Canada. The Industrial Revolution brought hard times to Scotland, and the lure of Canada’s wealth of resources beckoned. Many Highlanders were encouraged to move to Lanark County, Ontario, where they were granted 100 acres per family and given seed and farm implements at cost with an advance of money to help them settle the land. Lanark and Dalhousie counties were in fact, as the essay explains, originally Scottish military settlements.

In 1822 Walter Sim, husband to Hannah Harrower, traveled across the sea along with younger her brothers George (17) and Andrew (14). Their trip from Quebec to Montreal by steamship, then from Montreal to La Chine by wagon & foot (10 miles), and onward to Prescott with small flat-bottomed floatillas 120 miles up river, brought them to a meeting place where earlier pioneers met them with wagons. It was another 74 miles on land from Prescott to Lanark which took an additional 5 days. This difficult journey rewarded them with newly-surveyed crown land that they were assigned to make livable. Walter and George each were given 100 acres at lot 9, concession 4 in North Sherbrooke (Walter, the east half, George, the west) and Andrew shared the lot with his brother, the three of them likely working together to clear the land and construct their log shanty. Five years later, John McDonnell joined them taking up the east half of lot 12, concession 4. Later he received two more lots in Palmerston.

The last of the Harrower family to arrive in Canada, Walter’s wife Hannah, came from Scotland accompanied by Walter and their children in 1832. Walter had gone back to fetch her nine years earlier, but her father, the great James Harrower who was described earlier, was ill and she would not leave him alone. His wife and other children seemed no longer in existence, so they waited until conditions were more favourable to make the long trip. James, however, died the night before they left at age 79. While Walter was away, George had worked his half of the lot and had petitioned for it to be made his. This caused a bit of a family rift where Walter, who complained that this was not done with his consent, was forced to take up another property- lot 19, concession 2.

Later, in 1833, all 4 Harrower children (Margaret McDonnell, Hannah Sim, George and Andrew Harrower) attempted to appeal to the government that their land be granted to them for free because of their father’s service to the British Army during the Revolution. Because he was not living in America prior to his war service (as he came over from Scotland), he could not technically qualify as a United Empire Loyalist. They were not granted their claim. Despite this, they all stayed in the region: Andrew in Warwick county with his wife Sarah Williamson, their many children, and a child from his first wife Betsey Stokes; George in Lambton with his wife Eliza Williamson and their 8 children (they are buried in the pioneer cemetery); Walter and Hannah Sim stayed in North Sherbroke with their 8 children and were joined by Walter’s brother Robert (they’re buried in Crawford Cemetery); and my ancestors Margaret and John McDonnell also maintained their lots in North Sherbrooke & Palmerston with many many children.

This essay came with a large family tree which mapped out many of the known descendants- quite a tangled web. Many other documents were included in Lindy‘s package which attempt to further flesh out this Harrower-McDonnell connection. It is difficult to trace John McDonnell‘s life in Scotland, but Lindy believes that we can follow Scotch naming traditions and make an educated guess that his parents may have been called Donald/Daniel and Elizabeth/Elspeth. Their first son, James, was named for Margaret‘s father James Harrower, so their second son, Donald was likely named for his paternal grandfather. Elizabeth, their first daughter could have likely been named for her paternal grandmother, as their second daughter, Ann had been named for Margaret’s mother Ann Tulloch. This tradition was followed with other children, so this may be a starting point for searching out Scottish records for John’s family. Some hints to the McDonnell mystery may also lie in his early Canadian life in Glengarry county where there were many McDonnells. There is a family story that John had a brother named Hugh who came over to Canada in 1820, and would have likely settled in Glengarry. Lindy also sent a copy of a letter that one of the previously mentioned authors, Barbara Knudsen, wrote to St. Benedict’s Abbey in Fort Augustus. She looked into where John and Margaret married in Scotland, seeking out church records trying to determine if this Abbey may have been the place. Unfortunately, the priest’s register of their time has not survived. The current priest did affirm Barbara’s belief that John was a Glengarry Catholic because they spelled their name with an “ell” at the end as opposed to “MacDonald”.

Other documents included in this package number maps of the Lanark county properties owned by the Harrower-McDonnell-Sim families, maps of Invernesshire, Scotland, photographs of some Harrower descendants, documents transferring property and further family data…too much to outline here. I will continue to sift through this fascinating history and add more to this story in the future.